Roth Contributions Are More Valuable Than You Think

By Jim Krapfel, CFA, CFP

February 1, 2024

An important decision most working people make each year is whether to contribute to their retirement accounts — think 401(k), 403(b), 457(b), and IRA accounts — on a traditional pretax or Roth post-tax basis. Over the course of decades of maximizing contributions, optimizing the selection could save you tens of thousands of dollars in taxes.

It seems most people believe pretax is the way to go. Indeed, although 89% of employers that sponsor a 401(k) plan allow workers to contribute to a Roth account, just 21% of employees do, and 72% opt for pretax contributions. In this financial planning blog I make the case for why Roth usage should be dramatically higher.

Many people believe that it makes sense to contribute to a Roth account when income is relatively low and contribute to a pretax account when income is relatively high. However, there are a multitude of less understood considerations that make Roth the better choice for all except those within their peak earnings years.

1st Consideration: Tax Rate Optimization between Contributing and Withdrawing

The most obvious consideration is what your marginal tax rate is now versus what it is likely to be when you withdraw, or take a “distribution,” from your retirement account. Ignoring other worthy considerations (discussed later), you want your money to be taxed at the lowest possible rate, whether that is at time of contribution in the case of a Roth account or at time of distribution in the case of a pretax account.

Which contribution option is favored if my marginal tax rate at the time of distribution is the same as now?

Let us compare how this mathematically plays out under a theoretical pretax versus Roth 401(k) contribution scenario. In my pretax scenario, let’s say you (1) at the beginning of each year for 20 years you contribute $23,000, the maximum allowed for people under 50 years old in 2024 (if you are at least 50, then you are allowed an extra $7,500 “catch-up” contribution); (2) you are in the 32% marginal income tax bracket both now and when you fully liquidate the 401(k) penalty-free at the end of the 20th year; and (3) generate 7% annual returns.

When you use pretax funds to make a retirement contribution, you immediately save taxes at your marginal tax rate, in this case 32%, or $7,360. Here I assume you have the willingness and ability to use the $7,360 saved each year to invest in a taxable brokerage account that appreciates at the same 7% rate. Further, this account is liquidated at the same time as your 401(k) is distributed, and the long-term capital gains tax rate (for investments held at least one year) applied to your profits is 15%. I then compare the total after-tax account values in our pretax contribution scenario to that of our Roth contribution scenario.

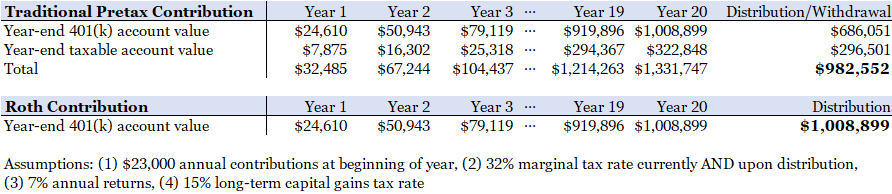

Figure 1: Marginal Tax Rate Analysis of Pretax versus Roth Contributions

Source: Glass Lake Wealth Management analysis

As you can see, you are over $26,000 worse off (2.6%) when contributing pretax dollars despite using the same marginal tax rate at time of contribution and time of distribution. This is because when you sell investments in your taxable account, you must pay taxes on your profits. With Roth accounts, none of the money is ever taxed if it has been in the Roth account for at least five years (if less than five years, then the earnings portion may be subject to income tax).

The degree to which future marginal tax rates need to be lower than current rates to reach economic parity depends on the degree of realized capital gains in your taxable account and your long-term capital gains tax rate. The greater the realized gains and the higher the capital gains tax rate, the lower the marginal tax rate needs to be at time of distribution to reach breakeven.

Varying the assumptions over multiple decades, you generally need a 2-4 percentage point lower marginal tax rate at time of distribution to breakeven. Alternatively, if you never sell anything in your taxable account and leave it to charity or your heirs (who receive a step-up in cost basis at time of death), then you would be economically neutral in my illustration.

How should I estimate my marginal tax rate at time of distribution?

Your future marginal tax rate will depend on (1) your taxable income and (2) prevailing tax brackets. Taxable income sources could include employment income if for you or your spouse work later in your lives, dividend and interest income from your brokerage accounts, capital gains from your brokerage accounts stemming from portfolio churn and funding your lifestyle in retirement, Social Security income, pension income, and passive income such as real estate.

Importantly, the size of your pretax retirement accounts can supercharge your taxable income later in life because unlike Roths, you must take “required minimum distributions” (RMDs) from pretax retirement accounts starting at age 73 (unless you are still employed in your current 401(k) and your employer does not require distributions). The RMD is based off the IRS’ Uniform Lifetime Table, and rises each year. For instance, a 73-year old with a $2 million pretax IRA at the end of 2022 would have had to distribute $75,472 by the end of 2023, and an 85-year old with the same balance would have had to distribute $125,000. These distributions become fully taxable “ordinary” income, potentially putting you in an unfavorable marginal tax bracket.

Meanwhile, predicting the makeup of tax brackets far into the future is difficult. However, we know that current tax rates are historically low, especially for higher earners, as depicted below. The United States’ fiscal situation, with ballooning public debt as a percent of GDP and Medicare and Social Security spending, augur for higher tax rates in the decades to come. Closer in, personal income tax rates will revert to higher levels in 2026 if provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are allowed to expire.

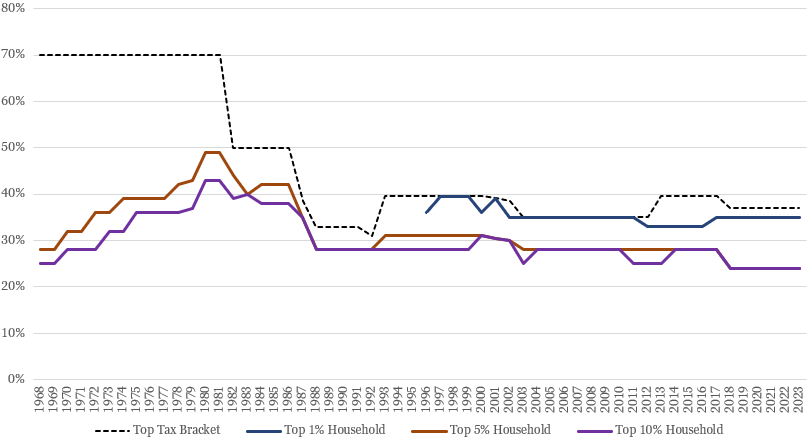

Figure 2: High Earners’ Marginal Tax Rates are Low by Historical Standards

Sources: DQYDJ. https://dqydj.com/household-income-by-year/ which cites U.S. Census Bureau data (historical household income percentiles). Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/federal/historical-income-tax-rates-brackets/ (historical federal income tax brackets). Glass Lake Wealth Management analysis

Note: For enhanced historical comparability, household incomes were compared to marginal tax rates of married filing jointly households. True marginal tax rates for a given percentile household are equal to or higher than what is depicted in the chart because some households consist of a single person who have higher marginal tax rates for a given income level.

2nd Consideration: Lack of Pretax IRA Money Allows for Backdoor Roth IRA Execution for High Earners

As highlighted in my “A Backdoor Roth IRA Could Pad Your Retirement” blog post, there is a legal maneuver to get money into a Roth IRA when your income is too high to do so directly. In 2024, key taxable income thresholds are $146,000 for a single person and $230,000 for a married couple, with any income above that amount reducing the amount you can contribute to a Roth IRA. At $161,000 and $240,000 income levels, respectively, no Roth IRA contributions are allowed.

You can circumvent the income limits of Roth IRA contributions by first contributing after-tax dollars to a traditional IRA, then executing what is a called a Roth conversion to your Roth IRA. As detailed in my original blog post, this is effective only when you do not have money in any pre-tax IRA accounts (assets in pre-tax 401(k)s and Roth accounts are okay).

Accordingly, strictly making Roth contributions to your retirement accounts prevents this issue from ever arising. If you already or plan to have assets in a pretax IRA, it could make sense to do a Roth conversion as explained in my “Roth Conversions Can Really Pay off, if Timed Well” blog post.

3rd Consideration: Other Tax Implications Upon Pretax IRA Distribution

There are a several reasons why suppressing taxable income via a Roth are beneficial beyond the direct effects of putting you in a higher marginal tax bracket:

1) Higher tax rate on investments when income reaches certain thresholds

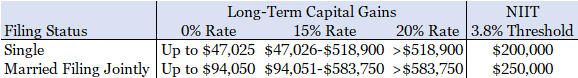

When your income increases, not only could you reach a higher marginal tax bracket, but you may also be subject to higher taxes on your investments. For instance, the long-term capital gains tax rate can trip from 0% to 15% or to 20% once your taxable income exceeds the below thresholds. What’s more, certain filers must pay a 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) on top of the normal tax, which applies to common non-wage income sources such as short-term and long-term capital gains, dividends, taxable interest, and rental income. Note the NIIT has not been indexed to inflation.

Figure 3: Long-Term Capital Gains Rates and NIIT Thresholds in 2024

Sources: SmartAsset. “2024 Capital Gains Tax Rates.” https://smartasset.com/taxes/2021-capital-gains-tax-rates. Charles Schwab. “What’s net investment income—and how is it taxed?” https://www.schwab.com/taxes/net-investment-income-taxes.

The prospect of higher tax rates on your investments could favor pretax or Roth contributions. Which option is advantaged depends on your other income amounts and the trajectory of your investment income. Although your total income ought to be higher in your working years, you are likely to generate greater investment income later in your life when your account balances are higher and you start selling some of your investments to fund your lifestyle in retirement.

2) Increasing proportion of Social Security benefits become taxable when income reaches certain thresholds

Social Security taxability also increases as income rises. Thresholds are based on what is called “combined income,” which equals adjusted gross income + nontaxable interest + ½ of your Social Security benefits. Up to 50% of your Social Security benefits are taxed when your combined income is $25,000 to $34,000 if single and $32,000 to $44,000 if married. Up to 85% of your Social Security benefits become taxable when combined income exceeds $34,000 and $44,000, respectively.

As you can see, it does not take a lot of income to reach 85% taxability. That is because these thresholds have not changed since 1983. I believe there is a good chance the thresholds increase in the years and decades ahead as the chorus gets louder on so many households being subject to taxability of Social Security benefits. As such, I would not dismiss the benefit of keeping taxable income low for higher income, Social Security-collecting households.

3) Medicare Part B and Part D premiums get more expensive when income reaches certain thresholds

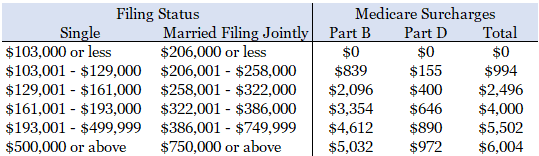

When you enroll in Medicare Part B (outpatient medical coverage) and Part D (prescription coverage) at age 65, the premium you pay partly depends on your income level. As laid out below, the annualized monthly surcharge can vary widely, which gives Roth accounts a distinct edge. Note that the surcharges payable in the current year are based on adjusted taxable income from two years prior, and the thresholds are indexed to inflation.

Figure 4: Annualized Monthly Surcharges for Medicare Coverage in 2024

Source: Medicare.gov. “2024 Medicare Costs.” https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/11579-medicare-costs.pdf

4th Consideration: Tax Considerations for Non-Spouse Beneficiaries

A final consideration is the taxability of your retirement accounts when you die. If you die with a spouse still alive, those assets transfer to the spouse tax-free. However, when your pretax retirement assets eventually transfer to someone other than your spouse, that beneficiary generally must distribute all the money from the account over 10 years. Only a disabled or chronically ill person, child of the deceased who has not reached age of majority (21 years old), or a person not more than 10 years younger than the retirement account owner can take RMDs based on their life expectancy. Once again, these distributions are fully taxable.

Meanwhile, inheritors of Roth retirement accounts are generally subject to the same distribution requirements as inherited traditional IRA accounts, but withdrawals are fully tax free as long as the Roth account is at least 5 years old.

The key point here is to be cognizant of who will be inheriting your retirement accounts. If you and/or your spouse’ beneficiaries are likely to be someone amid their high earnings years, then you could save them a lot in taxes by sticking largely to Roth contributions. If your retirement accounts mostly contain pretax money at time of death, then the requirement to drain the accounts within 10 years of inheritance could push your working beneficiaries into a top income tax bracket.

Bottom Line

Comparing your current marginal tax rate to what it is likely to be upon distribution is an important consideration when deciding between a pretax or Roth retirement contribution. To that point, you probably need a 2 to 4 percentage points lower marginal tax rate upon distribution to put pretax contributions on par with Roth contributions because of capital gains taxes on your brokerage account. Further supporting the Roth option, future tax rates for higher earners seem likely to increase.

Critically, one should look beyond a marginal tax rate evaluation when making this important decision. There is a multitude of other Roth account benefits, including (1) allowance for Backdoor Roth IRA execution; (2) money saved on investment income, Social Security benefits, and Medicare premiums in retirement; and (3) good chance your retirement account beneficiaries come out ahead.

Taking all these considerations into account, sticking to Roth contributions makes sense unless you are within your peak income years. Even when your earnings are relatively high, it can make sense to allocate a portion to Roth accounts such that pretax retirement balances, and ultimately ordinary income on distributions, do not become financially burdensome to yourself and your loved ones.

Disclaimer

Advisory services are offered by Glass Lake Wealth Management LLC, a Registered Investment Advisor in Illinois and North Carolina. Glass Lake is an investments-oriented boutique that offers a full spectrum of wealth management advice. Visit glasslakewealth.com for more information.

This blog is being made available for educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as an offering of advisory, tax, legal, insurance or accounting services or an offer to sell or solicitation to buy insurance, securities, or related financial instruments in any jurisdiction. Certain information contained herein is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Glass Lake Wealth Management believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions in which such information is based.