How to Optimize Health Savings Accounts Over a Lifetime

By Jim Krapfel, CFA, CFP

February 3, 2025

Those who are covered by a high-deductible healthcare plan (HDHP) have access to a wonderful retirement vehicle – the Health Savings Account (HSA). The “triple tax” savings – contributions are tax-deductible, funds grow tax-free, and withdrawals to pay for qualified healthcare expenses are tax-free – arguably make these accounts the best retirement vehicle around. But few people fully appreciate their benefits and maximize their usefulness. In this blog I explain exactly how HSAs work, what makes them so valuable, and how best to manage these accounts over a lifetime.

What are HSAs?

To contribute to an HSA, one must have healthcare coverage under a HDHP. For a plan to be considered high-deductible, it must have an annual deductible of at least $1,650 for self-only coverage or $3,300 for family coverage, and for which the annual out-of-pocket expenses do not exceed $8,300 for self-only coverage or $16,600 for family coverage. Among employers offering health benefits, 22% offer an eligible plan, with larger firms much more likely to offer coverage. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 51% of private industry workers participated in a HDHP in 2023, up from 45% in 2018.

In 2025, contribution limits for self-only and family HSAs are $4,300 and $8,550, respectively, with an additional $1,000 “catch-up” contribution allowed for individuals 55 or older. Unlike 401(k)s, these limits reflect employee + employer contributions. About 75% of eligible employers contribute dollars into their employees’ HSA, with an average contribution of $705 for single coverage and $1,297 for family coverage.

For spouses covered by separate self-only HDHP plans, each can contribute up to the maximum, self-only limit to their own, but can’t make up for any contribution shortfalls of the other spouse. For spouses in which one spouse is self-only and other is employee + children, the self-only spouse is limited to the self-only amount, and the spouse with family coverage can contribute up to the family limit. If both spouses are covered under the same plan, then either can contribute up to the family limit. Combination of both spouses’ contributions can never exceed the family limit.

HSA contributions may continue until the earlier of: (a) six months before the start of Social Security benefits (which can start at age 62-70); and (b) start of Medicare benefits (which can start 3 months before to 3 months after turning 65).

Like Flexible Savings Plans (FSAs), one can use HSAs to pay for qualified healthcare expenses such as doctor’s visits, drug prescriptions, and prescription eyeglasses (click here for a full list of qualified expenses), but not including plan premiums. Importantly, unlike FSAs, the balance in an HSA fully rolls over from year-to-year and stays with you if you change employers. If you withdraw HSA funds for non-medical purposes at any time, you will be taxed at your ordinary income tax rate. If you withdraw HSA funds for non-medical purposes prior to reaching 65, you will also be subject to a 20% penalty.

A majority of employers allow HSAs to be invested in securities like stock and bond funds, usually with a requirement of $1,000 to $2,000 set aside in cash to pay for monthly administrative fees. However, only 19% of HSA holders invest at all.

What Makes Them So Valuable?

The triple tax savings that HSAs provide cannot be found elsewhere. In other words, there is no other way to contribute pre-tax dollars AND have those dollars grow tax-free AND not face taxation upon their withdrawal, or distribution (when they are used for qualified healthcare expenses).

Further, it is one of the few ways higher income people can claim tax deductions. For instance, tax deductibility of traditional IRA contributions ceases when modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) reaches $89,000 for a single person, $146,000 for a married filing jointly person who participates in a retirement plan at work, and $246,000 for a married filing jointly person whose spouse participates in a retirement plan at work.

HSAs’ strong virtues are only contained by their low contribution limits. By comparison, each worker can contribute up to $23,500 to their 401(k) account with an additional $7,500 catch-up contribution allowed for people 50-59, and $11,250 for people 60-63. And that’s before the employer’s matching contribution.

Still, HSAs can become sizeable over one’s lifetime if fully contributed to annually, fully invested, and left untouched. Assuming a 23-year-old fully contributes to an HSA on every birthday through age 64, the contribution limit increases by 2.5% annually, and he or she invests the whole account with a 7% annualized return, then the HSA will have reached $1,605,510 at age 65. That is worth $569,128 in today’s dollars using a 2.5% annual inflation rate. Multiple that by two for a working couple.

Optimal Strategy Over a Lifetime

When enrolled in a HDHP, first be sure to contribute the maximum allowed every year. Once any 401(k) employer matching threshold is reached, prioritize HSA contributions over further 401(k) contributions. Remember to subtract any employer contribution from the total so you are not penalized for contributing too much.

I consider it a best practice to open, and send your contributions to, an HSA outside your employer’s provider. This is totally allowable and not well understood. Funding an outside account becomes essential to fully taking advantage of the triple tax savings if your employer does not offer HSA investment options to their workers. Even if your employer lets you invest, they tend to have more limited investment options than what you would be able to do on your own. Another benefit of funding an outside account applies to job changers. Rather than carrying a growing number of HSAs as you job hop, instead use one outside HSA as your primary account and then roll over any employer contributions from the employer-sponsored HSA when you leave that employer.

Once your account is open, be sure to invest the funds beyond the minimum amount you are required to carry in cash. Since your time horizon is long-term, you can invest similarly to how you would in your 401(k) account.

To the extent you can afford to do so, do NOT use your HSA to reimburse yourself for qualified healthcare expenses early in life. Instead, pay your healthcare costs out of pocket and leave the money in the HSA so it can continue to grow tax-free.

Critically, keep your healthcare receipts. Receipts from many years past can be used to substantiate eligibility of tax- and penalty-free withdrawals from your HSA if you get audited. Another pro tip is that you should deplete your HSA before you die because non-spouse beneficiaries of HSAs must pay tax on the entire account value in the year of the original owner’s death. This makes HSAs one of the worst types of accounts to inherit from a tax perspective.

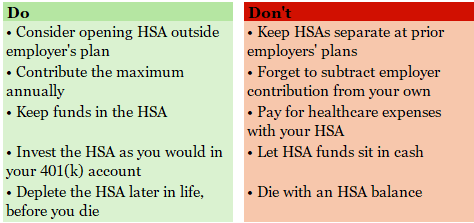

Figure 1: The Do’s and Don’ts of HSAs

Source: Glass Lake Wealth Management

Bottom Line

HSAs, with their triple tax savings, are a highly underappreciated retirement savings vehicle. Prioritize contributing the maximum to your HSA if you’re covered by a HDHP, do not tap the funds in your working years if you can afford to pay your healthcare expenses out of pocket, invest the funds to let it seriously compound over time, and reimburse yourself for a lifetime of incurred healthcare expenses late in life.

Disclaimer

Advisory services are offered by Glass Lake Wealth Management LLC, a Registered Investment Advisor in Illinois and North Carolina. Glass Lake is an investments-oriented boutique that offers a full spectrum of wealth management advice. Visit glasslakewealth.com for more information.

This blog is being made available for educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as an offering of advisory, tax, legal, insurance or accounting services or an offer to sell or solicitation to buy insurance, securities, or related financial instruments in any jurisdiction. Certain information contained herein is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Glass Lake Wealth Management believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions in which such information is based.